Neural networks are a regular topic on both tech sites and in the mainstream media. I decided to learn a bit about how they work.

When I tried to read chapter 1 of the book “Neural Networks and Deep Learning” things quickly turned… very mathy:

Not the most straightforward explanation! Maybe I should have read the about section of the book first :)

In this article I’ll try to give an introduction to neural networks that’s more friendly to web developers without a college education.

Let’s solve a simple problem

The article I mentioned above builds a neural network that’s able to recognize handwritten digits.

The network takes the pixels of the image of the written number as an input. The output is the classification of the digit as a 0, 1, 2, etc.

To save us some work, let’s pick a simpler problem. We’ll check if a number written in binary is even.

A few examples (numbers with a “b” suffix are in binary):

Input Output

========================

001b (1) 0 (Not Even)

010b (2) 1 (Even)

101b (5) 0 (Not Even)

Why use a neural network to solve this problem? It’s true, there are better solutions. But they won’t teach us anything about neural networks!

What is a neural network?

You can think of a neural network as a function that takes an array as a parameter and returns another array.

For our “isEven” neural network that means we take the binary digits as the input array (e.g. [0, 1, 0]) and return a simple true/false value (e.g. [1]).

If we did handwriting recognition the input array would contain the pixels of the photo. The return value would be an array with 10 values, representing buckets for each digit from 0 to 9. The highest number in the output array would show what digit the network thinks is written in the image.

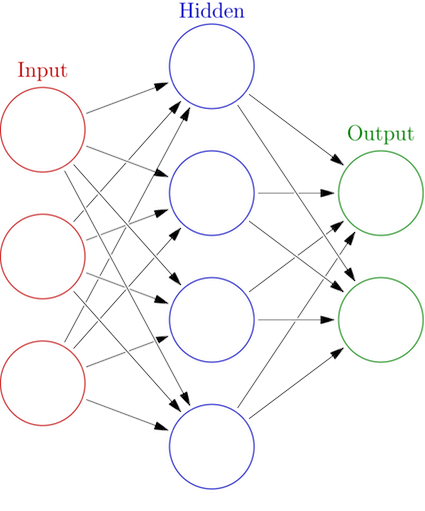

If you look up Artificial Neural Network on Wikipedia you’ll see this image:

Each column of circles represents something called a layer.

The input layer is the array we’re passing into our isEven function. The output layer is the return value… kind of.

While the input layer consists of just numbers, the output layer consists of neurons. A neuron takes an array of numbers and returns a single number. We’ll look at them in more detail later on.

So, the return value of our isEven function contains the results of the neurons in the output layer. (Which for isEven is only one neuron.)

Between the input layer and the output layer are one or more hidden layers, which also consist of neurons.

When we call the isEven function the numbers from the input array propagate through the network from left to right.

The hidden layer neurons take the input layer as an input.

The outputs from the neurons in the hidden layer become the inputs for the neurons in the output layer.

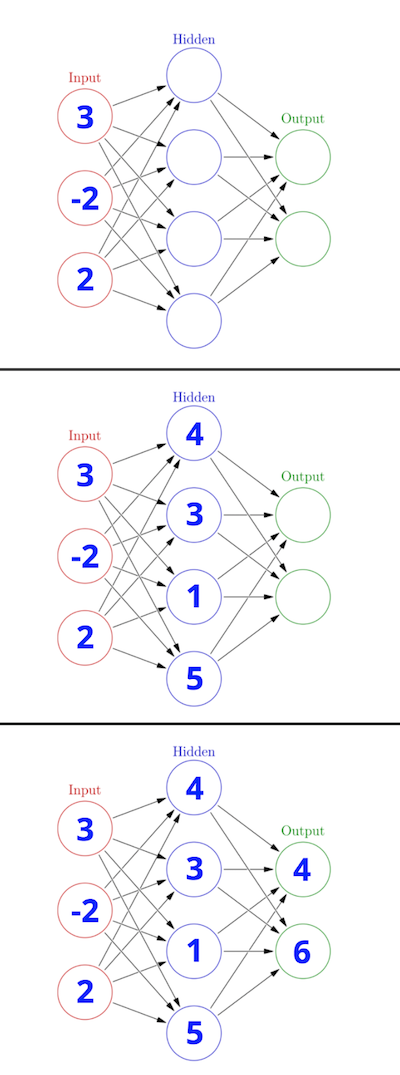

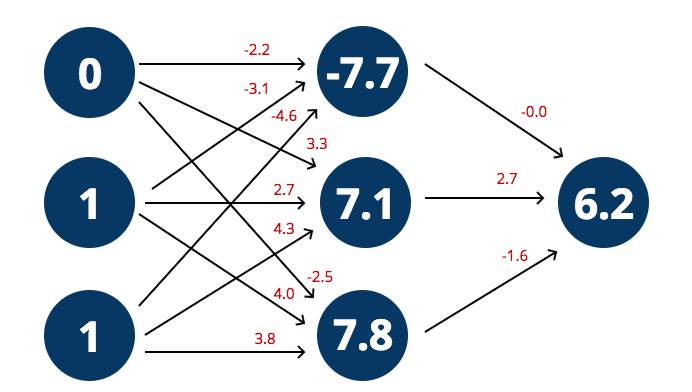

The image below shows how we progressively calculate the outputs for each layer. The exact values here don’t mean anything, we’ll look at them later.

How can our network learn to get better?

When programming, we normally tell the computer exactly what steps to take to solve a problem.

Specifying the exact rules for the computer to follow is easy if you want to check if a number is even. But in order to recognize a hand-written digit, manually coding the logic becomes quite difficult.

Instead, for neural networks we only specify a set of ground rules. For example, we need to decide how many neurons are in each layer, and how each neuron should behave.

What we don’t specify is the strength of the connections between the different neurons. Each connection has a weight that’s determined through learning.

In order for the network to learn we need a set of example data to train our neural network. Each example consists of the input to the network and the output we’re hoping for.

How well our network predicts the correct output for a given example depends on the weights it uses. During training we gradually adjust the weights in order to improve the network’s accuracy.

There’s an online demo on the TensorFlow website that illustrates these weight mutations really well.

There are two important observations to make when running the demo:

- The connections between the neurons become stronger or weaker

- The prediction of the network gradually becomes more accurate

What do the neurons do?

There are different types of neurons that behave slightly differently.

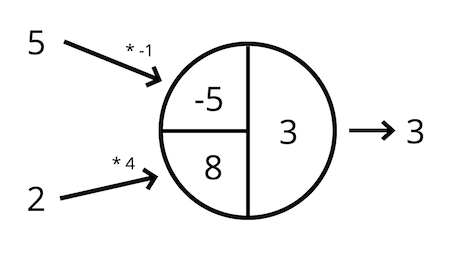

In the simplest case, a neuron multiplies each input value by the weight of the connection and returns the sum.

For example:

You can think of the numbers on the left (5 and 2) as the input layer. The circle then represents a hidden layer with a single neuron.

The output, 3, is then passed on to the next layer. We only have one hidden layer, so the next layer that follows is the output layer.

In JavaScript we can implement our neuron like this:

function Neuron(weights){

this.weights = weights

}

Neuron.prototype.process = function(inputs){

var sum = 0

for (var i=0; i<inputs.length; i++) {

sum += inputs[i] * this.weights[i]

}

return sum

}We pass the neuron a set of weights when we instantiate it. It then takes all the values from the previous layer to calculates its output value.

var neuron = new Neuron([4, -2, 6])

var output = neuron.process([1, 0, 1])

// output = 10In this example we’re using three input values and three weights. A binary number with three digits can only represent values up to 7.

When we actually run the network the input layer will contain 16 digits, letting us represent numbers up to 65,535.

Propagating the input values through the network

First, we need a set of weights to start with. We’re just going to pick random numbers.

We’ll store these numbers in a weights object that contains weights for the neurons in the hidden layer and in the output layer.

If we have three neurons in the hidden layer weights.hiddenLayer might look like this:

[

[ 1.5, -2.4, 3.8],

[ 0.3, -1.1, -2.3],

[-3.3, -1.2, -0.5]

]

Each hidden layer neuron needs exactly as many weights as there are values in the input layer. That’s 3 in the example above, or 16 later on.

The output layer also needs a weight for every value it receives from the previous layer. Since the hidden layer has three neurons that means we get three output values, and we need three weights for the neuron in the output layer.

This code makes a prediction for a given example input from our training data.

function predict(inputLayer, weights){

var neuronLayers = [

weights.hiddenLayer.map(neuronWeights => new Neuron(neuronWeights)),

weights.outputLayer.map(neuronWeights => new Neuron(neuronWeights))

]

var previousLayerResult = inputLayer;

neuronLayers.forEach(function(layer){

previousLayerResult = layer.map(neuron => neuron.process(previousLayerResult))

})

return previousLayerResult

}I could have called the function predictIsEven, but there’s nothing problem-specific about the code. What the network ends up predicting will depend on the data we use to train it.

For each layer, the predict function takes the result of the previous layer and passes it to the neurons in the current layer.

Let’s look at an example. Is 3 an even number? We convert the number to binary 011b before we ask the network to make a prediction.

var prediction = predict([0, 1, 1], getRandomWeights())

console.log(prediction)

// [ 6.259452749432459 ]

What does an output of 6.25 mean? We need to interpret the result of our network somehow.

I’m going to decide that an output greater than 0.5 means that the number is even.

But since 6.25 is greater than 0.5 that means or network is wrongly saying 3 is an even number!

To make a correct prediction we need training data that let’s us tweak the weights we’re using.

Training data

Normally, training data needs to be obtained manually. For handwriting recognition you ask lots of people to write down the numbers from 0 to 9. Then you take pictures of each digit and pass the images into the network. Once the network has made a prediction you can compare it to the number the person actually wrote down.

Conveniently, we can determine if a number is even without resorting to neural networks. Rather than collecting training data ourselves we can write a generateTestData function that generates the training data for us.

If we go through all our training examples and check what percentage of predictions is correct we can find a way to compare different sets of weights. That way we can determine the configuration that makes our network most performant.

Training our network

So let’s try some weights and see what works best!

This is the brute force solution. We’ll pick random weights, see how well they work, and keep track of what weights worked best.

We’ll do this 20,000 times. If the random set of weights is better than any other weights we had before we store them in bestWeights and show the new best correctness in the console.

The exact code for getRandomWeights and getCorrectness isn’t too important, but you can find the full code on Github.

var ITERATIONS = 20000

var trainingSet = generateTestData(0, 100)

var weights, bestWeights

var bestCorrectness = -1

for (var i=0; i<ITERATIONS; i++){

weights = getRandomWeights()

var correctness = getCorrectness(weights, trainingSet)

if (correctness > bestCorrectness) {

console.log("New best correctness:", correctness * 100, "%")

bestCorrectness = correctness

bestWeights = cloneObject(weights)

}

}And the console output:

New best correctness: 47 %

New best correctness: 50 %

New best correctness: 56 %

New best correctness: 65 %

New best correctness: 71 %

New best correctness: 81 %

New best correctness: 84 %

New best correctness: 86 %

New best correctness: 90 %

New best correctness: 95 %

New best correctness: 96 %

Nice! Our network makes a correct prediction in 96% of cases!

Assessing network performance

But wait… this just tells us the network is predicting our training examples correctly. But we want our network to be able to make a prediction for any number, even if it has never been trained with that exact number.

If we only look at correctness within the training set we can’t verify if the network actually learned what we wanted it to learn: how to identify even numbers.

A simple analogy is that the network could merely memorize the training data instead of building a deeper understanding.

We need to verify that the rules our network learned apply not only to the data it was trained with.

To do that we’ll use a set of example data that’s separate from the training set that we use to determine the weights.

That’s called a test set. Every time we think we found a better set of weights, we’ll calculate how well these new weights work for the test set.

var testSet = generateTestData(10000, 11000)

// ...

if (correctness > bestCorrectness) {

// ...

var testCorrectness = getCorrectness(weights, testSet)

console.log("New best correctness in training (test) set:",

correctness * 100, "%",

"(" + testSetCorrectness * 100 + "%)"

)

}Console output:

New best correctness in training (test) set: 47% (44.8%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 50% (50.0%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 56% (54.8%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 65% (56.2%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 71% (51.9%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 81% (73.6%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 84% (76.9%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 86% (81.6%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 90% (74.8%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 95% (54.4%)

New best correctness in training (test) set: 96% (80.5%)

It turns out that for numbers it wasn’t trained with our network is performing less well. Still, 80.5% is way better than random chance!

One problem with this particular dataset is that our training inputs aren’t representative of all possible input numbers. We trained the network with the numbers 0 to 99, which are all low numbers. However, the test set checks how well the network works for the numbers from 10,000 to 10,999.

Therefore, one way to improve our network would be to randomly select training examples from the full 0 to 65,535 range.

Try it

The full code is on Github, or you can try the code on JSFiddle.

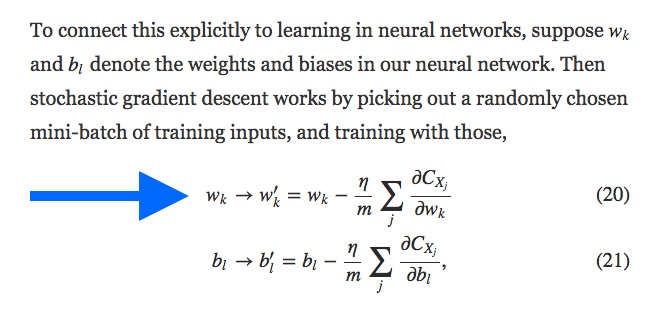

Backpropagation, or why people use math

It may surprise you to hear that our approach to determine good weights isn’t very efficient. :)

That’s why, in practice, people use math to figure out how to tweak the weights. You still start with random weights and then iterate, but the learning process is much more efficient.

If you take another look at the screenshot from above you can see that the formula shows how to go from a weight wk to a better weight wk’.

The algorithm that’s used to determine the improved set of weights is called backpropagation.

Other simplifications

There are a few things I’ve simplified for this article:

- Instead of measuring correctness (correct/incorrect) neural networks normally calculate a more nuanced error that indicates how far off the network’s predictions was.

- I’m using an object model, but normally these calculations are done with matrices.

- Neurons have an activation function.

- In addition to weights, neurons have a bias (that’s what the bl is for in the other formula above).

Keep in mind that I don’t have the best understanding of neural networks myself. But hopefully you learned something from this article.

If you’ve got more time to learn about neural networks, go read the article I mentioned earlier. It’s good, but it requires a bit more thinking.