I’ve spent about a month learning about Facebook’s JavaScript framework React. This article describes what makes it different from other JavaScript frameworks and how immutablility fit into the picture.

What does React do?

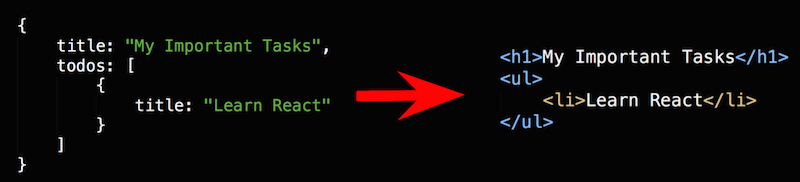

To me, React is all about mapping data to HTML code. In their most basic form, React components (views) are a function that takes data and outputs DOM elements:

Here’s an example of the render function of a React component:

render: function(){

var todo = this.props.todo;

return <li>{todo.title}</li>

}(props is the component data in this case. The return statement uses JSX syntax which makes it easier to generate HTML code inside JavaScript.)

What happens if the data changes? Most traditional frameworks would append another li to the list of todo items.

React, however, doesn’t encourage you to directly modify the DOM. The UI only changes when the underlying data changes. So to update the UI you must update the data.

And then React re-renders everything!

Isn’t re-rendering everything really slow?

There are two reasons why this doesn’t negatively impact React’s performance.

Firstly, the virtual DOM. When React renders a component it doesn’t just dump the HTML into the page body. Instead, it constructs its own DOM representation internally.

Once the internal rendering process is complete, React compares the virtual DOM to what already exists on the page. It then only updates the parts of the page that have changed since the last rendering process. This process is called reconciliation.

Secondly, one of the core insights behind React and the virtual DOM is that DOM manipulation is slow, but running JavaScript code is fast.

JavaScript engines are heavily optimized, so doing a full re-render and diffing the new virtual DOM to the previous virtual DOM isn’t very costly.

(React doesn’t compare to the actual DOM, so it won’t notice any changes you might have made to the DOM outside of React.)

As a result, React is actually very performant.

Preventing a full re-render with shouldComponentUpdate

By default, React calls the render method of every component on the page every time the data changes.

Since JavaScript is fast this usually isn’t a problem. However, if you have many components with complex rendering logic, you don’t want to call render on a component if its data hasn’t changed.

React’s solution to this is the shouldComponentUpdate method. It’s a function on a React component, just like render.

You need to implement shouldComponentUpdate so that it returns false if the component data hasn’t changed.

For example, you could do a deep comparison between the previous data and the new data, to see if anything has changed.

The app in this video logs calls to the render method and shows how the behavior changes when using shouldComponentUpdate:

</span>

When shouldComponentUpdate is used only the components whose data has changed are re-rendered.

Using immutable data to avoid a deep comparison in shouldComponentUpdate

The problem with manually checking if the data has changed is that it’s computationally expensive and might not be much faster than re-rendering the component.

Immutable data can provide a solution to this problem. Take this code using Immutable.js as an example:

a = Immutable.Map({"greeting": "hi"});

a.set("greeting", "hello")

a.get("greeting");

// => "hi"An immutable object can’t be modified. Instead calling .set returns a new object:

a = Immutable.Map({"greeting": "hi"});

b = a.set("greeting", "hello")

b.get("greeting");

// => "hello"And now it’s easy to check if our data has changed:

a === b

// => falseIsn’t creating a new object for every mutation expensive?

Working with immutable data is significantly slower than using JavaScript’s native JavaScript objects.

In practice, however, object mutation is unlikely to be a bottleneck. Other calculations and DOM rendering are a lot more expensive.

Immutable.js also re-uses the parts of an object that haven’t changed. This is called “structural sharing”.

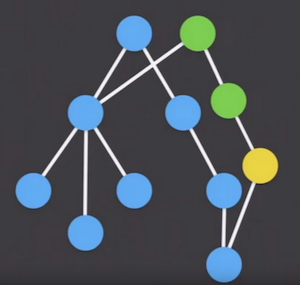

This picture (taken from a great talk by Lee Byron) illustrates structural sharing. The yellow dot represents a mutation deep inside the tree.

Other benefits of structural sharing

Another benefit of structural sharing is that data that isn’t mutated retains its reference.

For example, our todo app could have this data using Immutable.JS:

var data = Immutable.fromJS({

title: "My Todos",

todos: [

{

title: "Bake Cake"

}

]

})We can use the updateIn function to add another todo item. Here Immutable.JS is less pleasant to work with than native objects, where we could just call data.todos.push().

var data2 = data.updateIn(["todos"], function(todos){

return todos.push(Immutable.Map({title: "Clean Kitchen"}));

});We can now use a simple reference comparison to detect whether our data has changed:

data === data2

// => falseThe list of todos has also changed:

data.get("todos") === data2.get("todos")

// => falseBut, the first todo hasn’t changed, it’s still the same object!

data.getIn(["todos", 0]) === data2.getIn(["todos", 0]

// => trueThis makes it easy to re-render the components where the underlying data has changed, while skipping updates where the data remains the same.

Using Immutable with React

If you’re using Immutable.js, a reference comparison in shouldComponentUpdate is enough to determine if a component’s data has changed. You can also use the PureRenderMixin to avoid having to compare data manually.

Check out this repository demonstrating Immutable data and shouldComponentUpdate.